Banking System in India

The Dynamic Landscape of Indian Banking: A Comprehensive Overview

India’s banking system is the backbone of its rapidly expanding economy, a complex and multifaceted structure that has evolved dramatically over centuries. From its nascent stages rooted in indigenous banking practices to the sophisticated, technology-driven behemoth it is today, Indian banking has played a pivotal role in the nation’s economic development, financial inclusion, and global integration. Understanding this intricate system is crucial for anyone looking to grasp the nuances of India’s economic journey, whether they are investors, policymakers, students, or ordinary citizens. This comprehensive article delves deep into the history, structure, regulatory framework, challenges, and future prospects of the Indian banking sector, providing an exhaustive overview of one of the world’s most dynamic financial landscapes.

The journey of Indian banking is a compelling narrative of resilience, adaptation, and growth. It has navigated colonial influences, post-independence nationalization drives, liberalization reforms, and the current era of digital disruption. Each phase has left an indelible mark, shaping the institutions, policies, and practices that define the sector today. As India continues its trajectory towards becoming a global economic powerhouse, the banking system remains at the forefront, facilitating trade, investment, savings, and credit, thereby empowering millions and fostering national prosperity.

This article aims to provide an SEO-friendly, in-depth analysis, incorporating key terms and concepts relevant to the Indian banking sector. We will explore the various types of banks, the critical role of the Reserve Bank of India (RBI), the impact of government policies, the challenges of non-performing assets (NPAs), and the transformative power of FinTech. By the end, readers will have a robust understanding of how India’s banking system functions, its historical context, its present strengths and weaknesses, and its exciting future potential.

A Brief History of Indian Banking:

The story of Indian banking is as old as its civilization, evolving from informal money lending and indigenous banking systems to a sophisticated modern financial architecture. Understanding this historical trajectory is key to appreciating the current state and future direction of the sector.

Ancient and Medieval Banking Practices: Long before the arrival of Europeans, India possessed a well-developed system of indigenous banking. Merchants and wealthy individuals acted as moneylenders (mahajans, seths, shroffs), facilitating trade and commerce through various instruments. “Hundis,” a form of credit instrument, acted much like modern bills of exchange, allowing for the transfer of funds across vast distances without the physical movement of cash. These hundis were trusted, accepted widely, and formed the backbone of financial transactions during various empires, including the Mauryan, Gupta, and Mughal periods. Guilds also played a significant role, managing communal funds and extending credit to members. The concepts of deposits, loans, and interest were well-established, reflecting a vibrant pre-modern financial landscape.

Colonial Era: The Genesis of Modern Banking: The arrival of European trading companies marked a turning point. The British East India Company, and later the British Crown, introduced formal banking structures. The first modern bank in India was the Bank of Hindustan, established in Calcutta in 1770, though it failed by 1832. This was followed by the establishment of the Presidency Banks – Bank of Bengal (1806), Bank of Bombay (1840), and Bank of Madras (1843). These banks were crucial for funding the East India Company’s trade and administration, issuing currency notes, and managing government accounts.

As the 19th century progressed, several other banks were established, many by Indians, like the Allahabad Bank (1865) and Punjab National Bank (1894). A significant consolidation occurred in 1921 when the three Presidency Banks merged to form the Imperial Bank of India, which later became the State Bank of India in 1955. This period also saw the establishment of the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) in 1935, based on the recommendations of the Hilton Young Commission, to regulate the currency and credit system of the country.

Post-Independence Era: Nationalization and Directed Credit: After gaining independence in 1947, India faced the challenge of economic development and ensuring equitable access to credit. The banking sector, largely controlled by private entities, was perceived as serving only industrial and urban needs, neglecting agriculture and small-scale industries. To address this, the government embarked on a path of nationalization. The Imperial Bank of India was nationalized in 1955 and renamed the State Bank of India. The most significant move came in 1969 when 14 major private sector banks were nationalized, followed by another 6 in 1980.

The primary objectives behind nationalization were:

- Financial Inclusion: To channel credit to neglected sectors like agriculture, small-scale industries, and rural areas.

- Preventing Concentration of Wealth: To curb the control of large industrial houses over the banking system.

- Mobilization of Savings: To encourage savings among the masses and deploy them for national development priorities.

- Branch Expansion: To rapidly expand banking services into unbanked and underbanked regions.

This era saw an unprecedented expansion of bank branches, particularly in rural areas, and the introduction of “priority sector lending,” where banks were mandated to lend a certain percentage of their advances to specific sectors.

Liberalization and Reforms (1991 onwards): The Indian economy faced a severe balance of payments crisis in 1991, prompting widespread economic reforms, including in the banking sector. The Narasimham Committee reports (1991 and 1998) laid the blueprint for these reforms. The key objectives were to make the banking sector more efficient, competitive, and globally compliant.

Major reforms included:

- Entry of New Private Sector Banks: Licenses were issued to new private banks (e.g., ICICI Bank, HDFC Bank, Axis Bank), fostering competition.

- Reduction in Statutory Pre-emptions: Cash Reserve Ratio (CRR) and Statutory Liquidity Ratio (SLR) were gradually reduced, freeing up more funds for lending.

- Interest Rate Deregulation: Interest rates were largely deregulated, moving away from administered rates.

- Improved Prudential Norms: Introduction of international prudential norms like capital adequacy (Basel norms), asset classification, and provisioning.

- Establishment of Debt Recovery Tribunals (DRTs) and Asset Reconstruction Companies (ARCs): To address the growing problem of non-performing assets (NPAs).

- Greater Operational Autonomy: Public sector banks were given more autonomy in their operations.

These reforms transformed the Indian banking landscape, making it more robust, competitive, and responsive to market forces.

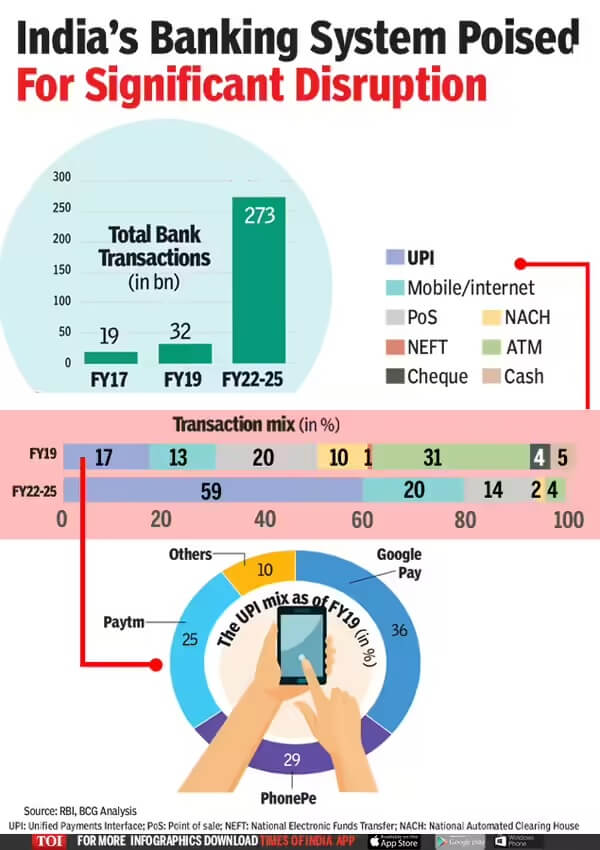

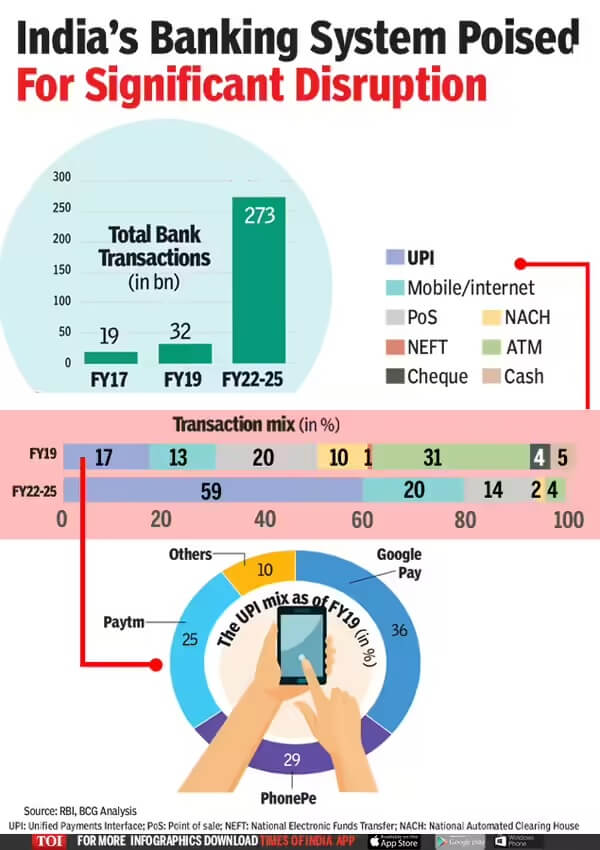

The Digital Revolution and Recent Trends: The 21st century has ushered in an era of unprecedented technological disruption. Indian banking has embraced digital transformation with remarkable speed and scale. Initiatives like the Unified Payments Interface (UPI) have revolutionized retail payments, making India a global leader in real-time digital transactions. The proliferation of mobile banking, internet banking, and the entry of new-age payment banks and small finance banks have further democratized access to financial services.

Recent trends include:

- Consolidation of Public Sector Banks: The government has undertaken mega-mergers of PSBs to create larger, more efficient, and globally competitive banks.

- Emergence of FinTech: A vibrant FinTech ecosystem is challenging traditional banking models and driving innovation.

- Focus on Cybersecurity: With increased digitization, cybersecurity has become a paramount concern.

- Sustainable Finance: Growing emphasis on green banking and financing sustainable development goals.

This continuous evolution underscores the dynamic nature of India’s banking system, constantly adapting to meet the changing needs of its economy and population.

The Indian Banking System is a robust and highly structured framework, with the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) at the apex, overseeing a diverse network of commercial, co-operative, and differentiated banks.

Reserve Bank of India (RBI): The Central Bank

The RBI is the central bank of India and the regulator of the entire banking system.

Functions

- Monetary Policy: Controls the money supply, interest rates, and inflation targets to achieve macroeconomic goals.

- Regulator and Supervisor: Licenses, regulates, and supervises all banks and financial institutions, ensuring financial stability and protecting depositors’ interests.

- Issuer of Currency: Sole authority for the issue of currency notes and coins (except one-rupee notes and coins, which are issued by the Government of India).

- Banker to Government: Manages the banking accounts of the Central and State Governments and acts as their debt manager.

- Banker to Banks: Maintains the accounts of all commercial banks, acts as a lender of last resort, and facilitates inter-bank settlements (e.g., through the clearing house function).

Organizational Structure

The overall direction of the RBI is vested in the Central Board of Directors, which is the highest decision-making body.

- Composition: It consists of 21 members:

- The Governor (Chairman) and four Deputy Governors (full-time official directors).

- Two representatives from the Ministry of Finance (Government officials).

- Ten directors nominated by the Government to represent various sectors (e.g., commerce, industry, finance).

- Four directors (one from each of the four Local Boards).

- Local Boards: The RBI has four Local Boards in Mumbai, Kolkata, Chennai, and New Delhi, which represent regional economic interests and advise the Central Board.

Scheduled Commercial Banks (SCBs)

SCBs are banks included in the Second Schedule of the RBI Act, 1934. This inclusion makes them eligible for certain privileges, like borrowing from the RBI at the Bank Rate, but also subjects them to mandatory compliance with the Cash Reserve Ratio (CRR) and Statutory Liquidity Ratio (SLR).

Categories

These are small financial institutions governed by both banking laws (RBI) and Co-operative Societies Act (State Registrar of Co-operative Societies). They primarily serve the credit needs of the unorganized sector, especially in rural areas.

- State Co-operative Banks (StCBs): Apex body at the state level.

- District Central Co-operative Banks (DCCBs): Operate at the district level.

- Primary Agricultural Credit Societies (PACS): The grass-roots level, dealing directly with individual members, mostly farmers.

- Urban Co-operative Banks (UCBs): Focus on urban and semi-urban areas, providing banking services to local communities and small businesses.

Payment Banks and Small Finance Banks (SFBs)

These are differentiated banks introduced by the RBI to further the goal of financial inclusion by catering to specific, unserved/underserved segments.

Their Role in Financial Inclusion

Both PBs and SFBs are licensed under Section 22 of the Banking Regulation Act, 1949 and are fully regulated by the RBI.

Banking Regulation Act, 1949

This Act is the fundamental legal framework governing the business of banking in India, administered primarily by the RBI.

- Purpose & Scope: It provides a legal basis for the licensing, regulation, and supervision of all banking companies. Key provisions include:

- Licensing: Mandatory license from the RBI to commence or carry on banking business.

- Management: Regulations on management structure, including the composition of the Board of Directors.

- Reserves and Capital: Stipulates Minimum Paid-up Capital and the mandatory transfer of a percentage of profits to a Reserve Fund (Section 17).

- Restrictions: Prohibits banking companies from engaging in trading and restricts certain forms of loans and advances.

- Branch Expansion: Requires RBI permission for opening new branches or shifting existing ones.

- Interface with Banks: Directly governs the day-to-day operations, financial structure, and management of Commercial Banks and Co-operative Banks (with modifications).

Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI)

SEBI is the apex regulator for the securities market and is responsible for protecting the interests of investors.

- Purpose & Scope: Its primary functions are Regulatory, Protective, and Developmental for the securities market. This includes:

- Market Integrity: Regulating stock exchanges, intermediaries (brokers, merchant bankers, etc.), and the conduct of business.

- Investor Protection: Preventing fraudulent and unfair trade practices, insider trading, and promoting financial education.

- Issuances: Regulating the raising of capital through public issues (IPOs, FPOs) by companies, including banks.

- Interface with Banks: Banks interact with SEBI in several ways, such as:

- When they launch their Initial Public Offering (IPO) or subsequent share issuances.

- When they act as depository participants, merchant bankers, or offer services related to the capital markets (e.g., mutual funds, custodial services).

- When they are listed entities on the stock exchange.

Insurance Regulatory and Development Authority of India (IRDAI)

IRDAI is the autonomous, statutory body governing the insurance sector in India.

- Purpose & Scope: Its mandate is to protect the interests of policyholders and to regulate, promote, and ensure the orderly growth of the insurance and reinsurance business. This covers:

- Licensing and Solvency: Granting licenses to insurance companies and ensuring they maintain the required solvency margin (financial stability).

- Product Approval: Regulating and approving insurance products and premium rates.

- Policyholder Grievances: Establishing mechanisms for the speedy settlement of genuine claims and addressing grievances.

- Interface with Banks: Banks have a strong interface through Bancassurance, where they sell insurance products (life and non-life) of an insurer to their customers. This is governed by IRDAI regulations. Additionally, IRDAI oversees banks’ subsidiary companies engaged in the insurance business.

Financial Stability and Development Council (FSDC)

FSDC is an apex-level, non-statutory council established by the Government of India.

- Purpose & Scope: It institutionalizes the mechanism for maintaining financial stability, enhancing inter-regulatory coordination, and fostering the development of the financial sector. Key mandates include:

- Macro-Prudential Supervision: Monitoring the macro-prudential health of the entire economy and the functioning of large financial conglomerates.

- Inter-Regulatory Coordination: Resolving regulatory issues where there are overlaps or gaps between financial sector regulators (RBI, SEBI, IRDAI, PFRDA, etc.).

- Financial Literacy and Inclusion.

- Composition: The FSDC is chaired by the Union Finance Minister. Its members include the Governor of RBI, Chairpersons of SEBI, IRDAI, PFRDA (Pension Fund Regulatory and Development Authority), IBBI (Insolvency and Bankruptcy Board of India), and key Finance Ministry secretaries.

- Interface: It acts as the super-regulatory coordination body where the heads of RBI, SEBI, and IRDAI (among others) meet to discuss systemic risks and policy coordination for the entire financial sector.

Financial inclusion in India is a multifaceted effort driven by government initiatives, ground-level agents, specialized institutions, and technological innovation.

Jan Dhan Yojana and its Impact

The Pradhan Mantri Jan-Dhan Yojana (PMJDY), launched in 2014, is a flagship national mission for financial inclusion. Its core objective is to ensure affordable access to financial services like basic savings and deposit accounts, remittances, credit, insurance, and pensions for every household.

Key Impact:

- Massive Account Ownership: PMJDY has resulted in the opening of over 500 million bank accounts, significantly increasing the percentage of adults with access to a formal bank account, particularly in rural and semi-urban areas, and among women.

- Direct Benefit Transfer (DBT): It created the foundation for the JAM Trinity (Jan Dhan-Aadhaar-Mobile), enabling the government to transfer subsidies and welfare benefits directly into beneficiary accounts. This minimizes leakage, increases transparency, and ensures timely payments.

- Financial Security: The scheme provides features like a RuPay debit card, an accident insurance cover (currently ₹2 lakh), and an overdraft facility up to ₹10,000 for eligible account holders, promoting a safety net for vulnerable populations.

- Increased Savings: The rising average deposit balance in PMJDY accounts is an indicator of increased usage and the inculcation of a savings habit among the previously unbanked.

Business Correspondents (BCs)

Business Correspondents (BCs), also known as Bank Mitras, are retail agents authorized by banks to provide banking and financial services in areas where opening a physical bank branch is not feasible or viable. They serve as the last-mile link between banks and the rural/underserved population.

Role and Functions:

- Account Opening and KYC: They help customers, especially in remote villages, with the preliminary processing of forms, account opening (including Basic Savings Bank Deposit Accounts/PMJDY accounts), and Know Your Customer (KYC) compliance.

- Cash-in/Cash-out (CICO): BCs use devices like Micro-ATMs to facilitate small-value cash deposits and withdrawals, overcoming the challenge of distance to bank branches.

- Remittances and Transactions: They handle the receipt and delivery of small-value remittances and enable other routine banking transactions.

- Financial Literacy and Cross-selling: BCs educate customers about financial products and cross-sell services like micro-insurance, micro-pension schemes, and small loans (like MUDRA).

Microfinance Institutions (MFIs)

Microfinance Institutions (MFIs) are non-bank entities that provide small-scale financial services, primarily microcredit (small loans), savings, insurance, and remittance services, to low-income households, micro-entrepreneurs, and individuals who are typically excluded from traditional banking.

Contribution to Financial Inclusion:

- Credit Access for the Poor: MFIs fill a critical gap by providing collateral-free small loans, mainly to women grouped in Self-Help Groups (SHGs) or Joint Liability Groups (JLGs), which is crucial for starting or expanding micro-enterprises.

- Poverty Alleviation and Women Empowerment: By facilitating income-generating activities and fostering entrepreneurship, microfinance acts as a powerful tool for poverty reduction and economic independence for women.

- Alternative to Informal Money Lenders: They offer an alternative to high-interest loans from local money lenders, protecting the poor from debt traps.

- Doorstep Service: Their field-based operational model ensures accessibility and frequent client interaction, leading to better repayment rates and financial discipline.

Role of Technology in Extending Reach

Technology has been the most significant accelerator of financial inclusion, enabling scale, efficiency, and lower costs in service delivery.

Key Technological Drivers:

- Aadhaar and Biometrics: India’s unique digital identity system, Aadhaar, combined with biometric authentication, simplifies the KYC process (e-KYC) and authenticates transactions (e.g., through Aadhaar Enabled Payment System – AePS), making financial services accessible even to those with low literacy.

- Unified Payments Interface (UPI): This instant real-time payment system, along with mobile banking, has revolutionized digital payments. It allows for seamless, 24/7 fund transfers using a simple mobile application, bringing millions into the digital transaction fold.

- Mobile and Internet Banking: The proliferation of mobile phones allows customers to conduct banking transactions, check balances, and make payments without visiting a bank branch, dramatically extending reach to remote and rural areas.

- Fintech Innovations: Fintech companies use Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML) for alternative credit scoring, enabling loans to individuals and MSMEs without traditional credit histories. Digital platforms are also used for delivering micro-insurance and wealth management products.

Challenges Facing the Indian Banking Sector:

The Indian banking sector faces several significant challenges across key areas, including asset quality, competition, security, capitalization, and governance.

Non-Performing Assets (NPAs)

Non-Performing Assets (NPAs) are loans for which the principal or interest payment has been overdue for 90 days or more.

- Causes:

- Internal Factors: Lax lending practices, poor credit appraisal and risk management, managerial deficiencies, and willful defaults by large borrowers.

- External Factors: Economic slowdowns leading to industrial sickness, regulatory bottlenecks in debt recovery, and delays in project implementation (especially in sectors like infrastructure).

- Consequences:

- Reduced Profitability: Banks must make provisions (set aside funds) for NPAs, reducing their net interest income and overall profits

- Constrained Lending: High NPAs erode the capital available for fresh lending, hampering credit growth and overall economic activity.

- Eroded Public Trust and potential liquidity issues if depositors lose confidence.

- Government and RBI Initiatives:

- Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code (IBC): A time-bound resolution process for financially stressed companies, shifting the focus from the borrower to the asset.

- Asset Reconstruction Companies (ARCs): Entities that buy bad loans from banks and financial institutions to help clean up their balance sheets.

- A-QIR (Asset Quality Review): Initiated by the RBI to push banks to recognize and provision for bad loans transparently.

Competition

The competitive landscape is rapidly evolving, putting pressure on traditional banking models.

- From FinTech Companies:

- FinTechs offer agile, customer-centric solutions, particularly in payments (UPI, wallets), lending (P2P platforms), and wealth management.

- They leverage technology and data analytics to offer a superior user experience and often lower operational costs.

- Traditional banks are compelled to invest heavily in digital transformation or partner with FinTechs to stay relevant.

- From New Banking Models:

- Neobanks (digital-only banks, often collaborating with traditional banks) and specialized banks like Payment Banks and Small Finance Banks are challenging the dominance of large commercial banks by focusing on specific segments or offering low-cost services.

Cybersecurity Threats

The rapid digitization of the banking sector has increased its vulnerability to cyber risks.

- Rising Digital Fraud:

- Threats include phishing, vishing, malware, ransomware, identity theft, and data breaches.

- The increasing volume of digital transactions, especially through platforms like UPI, makes them a lucrative target for fraudsters.

- Regulatory Responses (RBI):

- Issuing comprehensive Cyber Security Frameworks for banks, mandating the establishment of a robust Security Operations Center (SOC).

- Requiring mandatory vulnerability assessments, penetration testing, and timely reporting of cyber incidents.

- Emphasizing customer awareness programs on safe digital practices.

- Adherence to the Information Technology Act, 2000 and the Digital Personal Data Protection Act, 2023 for data security.

Capitalization Issues

Ensuring banks hold sufficient capital is crucial for financial stability.

- Basel III Norms and their Implications:

- Basel III is an international regulatory framework setting higher standards for bank capital adequacy, stress testing, and market risk.

- Implications: Banks are required to maintain higher Common Equity Tier 1 (CET1) ratios and introduce a Capital Conservation Buffer (CCB). This forces banks, particularly Public Sector Banks (PSBs), to raise substantial capital, which can strain their profitability and Return on Equity (ROE) in the short term.

- Government Recapitalization Efforts:

- The government has repeatedly injected capital, primarily through recapitalization bonds, into Public Sector Banks (PSBs) to help them meet Basel III norms and absorb NPA losses. This has been necessary because PSBs often struggle to raise capital from the market due to low valuations.

Governance and Management

Weak governance and risk practices are often at the root of financial distress.

- Board Effectiveness:

- Challenges include a lack of independence, professional expertise (especially in technology and risk management), and adequate oversight, particularly in PSBs where government influence can sometimes dilute accountability.

- Risk Management Practices:

- Need for more sophisticated and comprehensive Credit Risk models, moving beyond traditional collateral-based lending.

- Strengthening Operational Risk management to address vulnerabilities arising from digital adoption (e.g., cyber threats).

- Adopting global best practices and robust internal controls to align with modern financial complexity.

Technological Transformation and FinTech:

The intersection of Technological Transformation and FinTech is fundamentally reshaping the financial industry through various innovations. Here is a breakdown of the key elements you listed:

Digital Banking

Digital banking revolves around providing financial services remotely via the internet and mobile devices, enhancing convenience and accessibility.

Mobile Banking and Internet Banking: These channels allow customers to perform most traditional banking functions—such as checking balances, transferring funds, paying bills, and applying for loans—without visiting a physical branch.

UPI (Unified Payments Interface) and its success: UPI is an instant, real-time payment system that facilitates inter-bank peer-to-peer (P2P) and person-to-merchant (P2M) transactions through a simple mobile application.

Success: UPI has been a massive success, positioning its originating country as a global leader in real-time payments. It is an open, interoperable, and zero-cost system for end-users, leading to widespread adoption for daily, small-value transactions. This deep penetration drives significant financial inclusion and digital payment volumes.

IMPS, NEFT, RTGS: These are electronic fund transfer systems that remain crucial to the banking infrastructure:

IMPS (Immediate Payment Service): Provides instant, 24/7 interbank electronic fund transfer through mobile and internet banking.

NEFT (National Electronic Funds Transfer): A system for transferring funds from one bank account to another on a deferred net settlement (DNS) basis, typically settling in batches.

RTGS (Real-Time Gross Settlement): A system for the continuous settlement of funds transfers individually (on a gross basis). It is primarily used for high-value transactions due to its real-time nature.

Blockchain and Distributed Ledger Technology (DLT):

DLT is a decentralized database managed by multiple participants, ensuring data is tamper-resistant, transparent, and secure. Blockchain is a type of DLT.

Potential Applications in Banking:

Cross-Border Payments: Reduces the need for multiple intermediaries, cutting costs and settlement times from days to near-instantaneous.

Trade Finance: Simplifies complex, paper-heavy processes like Letters of Credit by creating a shared, immutable ledger accessible to all parties (banks, exporters, importers).

Security and KYC/AML: Provides a secure, shared digital identity (KYC) database and an immutable audit trail for transactions, which aids in Anti-Money Laundering (AML) and compliance efforts.

Asset Tokenization and Central Bank Digital Currency (CBDC): Facilitates the digital representation of assets (like real estate or bonds) on a blockchain and is the underlying technology for the issuance of central bank digital currencies (e.g., the Digital Rupee).

Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML):

AI and ML algorithms analyze vast datasets to automate tasks, predict outcomes, and personalize services.

Fraud Detection: AI/ML models analyze transactional and behavioral data in real time to identify anomalies and suspicious patterns that human analysts or rule-based systems might miss, significantly reducing financial losses and false positives.

Credit Scoring: ML models use both traditional (credit history, income) and alternative data (utility payments, mobile usage) to build richer borrower profiles. This provides more accurate risk assessments, helps in loan pricing, and promotes financial inclusion by accurately scoring individuals with limited traditional credit history.

Customer Service: AI-powered chatbots and virtual assistants handle a significant portion of routine customer inquiries 24/7, reducing response times, and improving customer satisfaction. They use Natural Language Processing (NLP) to understand and respond to diverse queries.

Robo-Advisors and Wealth Management:

Robo-Advisors are automated, digital platforms that provide algorithm-driven financial planning and investment management services with little to no human supervision.

Impact: They are disrupting traditional wealth management by offering services that are low-cost, accessible to a wider demographic (including retail and mass-affluent investors), and objective (devoid of human emotional bias or commission-driven advice).

Functionality: They typically use questionnaires to assess a client’s risk tolerance, financial goals, and time horizon to automatically create, manage, and rebalance diversified investment portfolios based on Modern Portfolio Theory.

Current Trend: Many firms now offer hybrid models, combining the efficiency and low cost of the algorithm with the complex advice and human touch of a traditional financial advisor for high-net-worth clients.

Open Banking:

Open Banking is a collaborative model where customer-permissioned financial data is shared securely between banks and third-party service providers (FinTechs) using APIs.

API-Driven Services: Application Programming Interfaces (APIs) act as digital connectors, allowing FinTechs to securely access banking data (with consent) to build new, innovative services like:

Personal finance management apps

Faster, automated loan application processes

Tailored insurance products

Account Aggregators (AAs): AAs are the specific regulatory framework in some countries (like India) that enable Open Banking. They are consent managers that facilitate the secure and electronic transfer of an individual’s or business’s financial data (e.g., bank statements, tax filings, investment records) from Financial Information Providers (FIPs) to Financial Information Users (FIUs).

Role: The AA system is data-blind (it cannot ‘see’ or store the data) and puts the customer in complete control of their data, making the sharing process digital, secure, and instantaneous. This facilitates quicker loan underwriting, personalized financial advice, and improved fraud prevention.

Impact of Government Policies and Global Economic Factors:

The influence of Government Policies and Global Economic Factors on the Indian financial system, particularly its banks, is profound and operates through several interconnected channels.

Monetary Policy Transmission

Monetary policy is set by the Reserve Bank of India (RBI), which uses tools like the Repo Rate to manage liquidity, inflation, and credit.

- Mechanism: Changes in the policy rate are intended to pass through the financial system via multiple channels:

- Interest Rate Channel: Policy rate changes affect money market rates, which should then influence banks’ lending and deposit rates.

- Credit Channel: Changes in banks’ cost of funds affect their willingness and ability to lend, thus impacting credit availability.

- Asset Price Channel: Monetary policy can influence asset prices (e.g., housing, equity), which affects corporate and household balance sheets and, in turn, their borrowing and spending.

- Government’s Impact: Government policies can affect the efficiency of this transmission:

- Small Savings Schemes: Government-administered high interest rates on small savings schemes (like PPF, NSC) force banks to keep their deposit rates higher to remain competitive, often impeding the smooth pass-through of RBI rate cuts to lending rates.

- Credit Demand: Government spending and overall fiscal health influence the aggregate demand and credit demand, affecting the final outcome of monetary policy actions.

- Structural Reforms: Regulatory changes like the introduction of the External Benchmark-based Lending Rate (EBLR) system (for loan pricing) have been government-backed moves to improve the speed and extent of monetary policy transmission to the end borrower.

Fiscal Policies and their Influence

Fiscal policies—government spending, taxation, and borrowing—have a direct influence on the banking sector and credit growth.

- Credit Growth:

- Stimulus/Capex: Expansionary fiscal policies, such as increased government capital expenditure (capex), boost economic activity and demand for goods and services. This, in turn, stimulates credit demand from businesses (corporate loans) and consumers (retail loans).

- Tax Policies (GST): Tax rate adjustments, like those in the Goods and Services Tax (GST), can directly affect consumer spending and business sentiment, immediately translating into an uptick or slowdown in credit for consumption and working capital.

- Crowding Out Effect: High fiscal deficits increase government borrowing. This raises the demand for funds in the market, which can drive up market interest rates and potentially ‘crowd out’ private sector borrowing by making it more expensive for banks to lend.

- Bank Solvency: Government-led recapitalization of Public Sector Banks (PSBs) improves their capital adequacy, enabling them to increase lending and clean up their balance sheets, thereby strengthening the financial system.

Global Economic Slowdowns and their Effect

As the Indian economy becomes increasingly integrated globally, external factors have a significant impact on Indian banks.

- Trade Contraction: A global slowdown reduces demand for Indian exports. Banks involved in trade finance (letters of credit, guarantees) face higher risks of defaults, and industries dependent on exports see a dip in revenue, leading to potential Non-Performing Assets (NPAs) for banks.

- Capital Flows: During a global economic crisis or slowdown (e.g., the Global Financial Crisis of 2008), investors in advanced economies often move capital to “safe-haven” assets, leading to a sudden reversal of Foreign Institutional Investment (FII) from emerging markets like India.

- This capital outflow causes the Indian Rupee (INR) to depreciate, making foreign currency-denominated loans and external debt more expensive for Indian companies, which raises their default risk on bank loans.

- Commodity Prices: Global slowdowns affect crude oil prices. Since India is a massive oil importer, falling global prices during a slump can be beneficial by reducing the import bill, easing inflationary pressure, and improving the Current Account Deficit (CAD), which indirectly supports the stability of the banking system.

Trade Wars and Geopolitical Events

Trade wars and major geopolitical events introduce significant market uncertainty and risk.

- Supply Chain Disruption: Events like the Russia-Ukraine conflict or prolonged US-China trade tensions disrupt global supply chains. This increases raw material costs (e.g., commodities, oil), leading to higher inflation in India and increased working capital needs for businesses, which can strain corporate balance sheets and banks’ exposure.

- Risk Aversion and Capital Flight: Geopolitical instability heightens global risk aversion. Similar to an economic slowdown, investors often pull capital out of emerging markets, leading to currency depreciation (Rupee weakens) and stock market volatility. Banks must manage the resultant pressure on their balance sheets and foreign currency exposure.

- Sanctions and Compliance: International sanctions (e.g., on Russia) directly impact Indian banks with foreign operations or those dealing with sanctioned entities. Banks must significantly ramp up their compliance and anti-money laundering (AML) monitoring to avoid being penalized by global regulators.

- Trade Finance Risk: Escalation of trade wars or diplomatic tensions increases the counterparty risk in international trade finance, making banks more cautious in lending for import/export activities.

Future Prospects and Outlook:

The future prospects for the Indian financial sector are defined by a mix of structural reform, digital disruption, and inclusive growth as it consolidates its position as a major player in global finance.

Consolidation in Public Sector Banks (PSBs)

Consolidation will continue to be a key theme, aiming to create fewer, but stronger public sector banks capable of meeting the economy’s growing credit demands and competing globally.

- Focus on Scale and Efficiency: The government is expected to pursue further mergers among mid-sized and smaller PSBs (e.g., potential mergers of Union Bank of India and Bank of India, or Indian Overseas Bank and Indian Bank) to eliminate overlapping networks, achieve economies of scale, and improve efficiency.

- Privatization: Discussions surrounding the strategic privatization of smaller PSBs, such as Bank of Maharashtra or Punjab & Sind Bank, are anticipated to unlock value and reduce the government’s footprint in the sector.

- Strengthened Governance: The overall goal is to enhance governance and financial health across the PSB segment, reducing the vulnerability of the system.

Emergence of “Neo-banks”

Neo-banks, which are digital-only platforms that partner with licensed traditional banks, are set for rapid growth by offering innovative, customer-centric, and low-cost financial services.

- Digital-First Experience: They leverage technologies like AI, Machine Learning, and UPI to deliver seamless digital banking services like instant account opening, superior customer service, and integrated payment solutions.

- Targeting Underserved Segments: Neo-banks are poised to cater to the unique needs of Micro, Small, and Medium Enterprises (MSMEs) and the digitally savvy population, providing alternative credit scoring and customized financial products.

- Regulatory Evolution: The growth of the segment will likely necessitate the evolution of standalone regulations from the RBI to manage this new category of digital service providers.

- Technology as a Catalyst: The use of Digital Public Infrastructure (DPI) like UPI and Aadhaar-enabled services, along with Payment Banks and Small Finance Banks, will continue to expand access to formal financial services for the unbanked and underbanked, particularly in rural and semi-urban areas.

- Comprehensive Access: Inclusion efforts will move beyond merely opening bank accounts to providing affordable and useful financial products like micro-credit, insurance, and investment to all sections of society.

- Poverty Reduction & Economic Growth: By enabling greater participation in the formal economy, financial inclusion will act as a major driver for poverty reduction and sustainable economic growth.

Regulatory Sandbox for Innovation

The Reserve Bank of India’s (RBI) Regulatory Sandbox will continue to be a crucial tool for fostering responsible innovation.

- Controlled Testing: It provides a safe, controlled environment for FinTech firms to test new products (like those in digital lending, fraud prevention, and cross-border payments) with real customers, mitigating risks before mass market launch.

- Regulatory Learning: The sandbox allows the RBI to test and refine regulatory frameworks in response to emerging technologies, ensuring consumer protection keeps pace with innovation.

- Boosting FinTech Investment: The structured approach lends confidence to investors and innovators, making the Indian FinTech sector more attractive for venture capital and global institutional investment.

India’s Role in Global Finance

India’s financial sector is rapidly enhancing its influence on the global stage.

- Capital Market Resilience: With a rising market capitalization, India is strengthening its position among the world’s top financial markets, attracting substantial Foreign Institutional Investment (FII).

- Exporting Digital Finance Models: India’s success with UPI and other digital public goods (IndiaStack) is setting global benchmarks, with several countries adopting or showing interest in replicating its real-time payments model.

- Global Integration: Indian banks are expanding their international presence, and the increasing strength of the economy is leading to greater cross-border trade and investment facilitation, cementing India’s role as an economic powerhouse.

Key References & Further Reading on Indian Banking

1. Policy, Regulation, and Institutional Sources

These official publications provide the foundational data, policy context, and regulatory framework for the Indian financial system.

- Reserve Bank of India (RBI) Publications:

- Report on Trend and Progress of Banking in India: An annual report offering comprehensive data, analysis, and an overview of the performance and operations of the Indian banking sector.

- Financial Stability Report (FSR): A semi-annual report that assesses the resilience of the Indian financial system.

- Enabling Framework for Regulatory Sandbox: Official documents detailing the RBI’s approach to fintech innovation and testing.

- Speeches and Working Papers by RBI Officials: Focus on specific topics like monetary policy, financial inclusion, or technology.

- Government of India Reports:

- Economic Survey of India (Annual): Features a detailed chapter on the financial sector’s performance and policy issues.

- Narasimham Committee Reports (1991 & 1998): Essential historical documents that laid the groundwork for major banking sector reforms.

- SEBI & IRDAI Publications: Regulatory guidelines and reports relevant to capital markets and the insurance sector, which are interconnected with banking.

2. Consolidation and Public Sector Banks (PSBs)

- Scholarly Articles/Journals: Search for papers titled “Consolidation in the Indian Banking Sector,” “Impact of Consolidation on PSBs,” or “Efficiency of Public Sector Banks.”

- Tip: Look for academic journals from institutions like IIMs, IITs, or reputed international finance journals that focus on emerging economies.

- Think Tank Reports: Reports from institutions like the National Council of Applied Economic Research (NCAER) or ICRIER on banking efficiency and mergers.

- News/Business Analysis: Detailed reports on the merger of 10 PSBs into four in 2020 and its subsequent impact.

3. FinTech, Neo-Banking, and Digital Transformation

- Academic Papers: Look for research papers on the “Rise of Neo-Banks in India,” “Digital Payments and UPI,” or “FinTech Innovation and Regulation.”

- Industry Reports: Publications by consulting firms such as KPMG, PwC, Deloitte, or Boston Consulting Group (BCG) often release annual or thematic reports on the “State of FinTech in India” and “Digital Banking.”

- National Payments Corporation of India (NPCI) Data/Reports: Official information regarding the scale and performance of UPI and other payment systems.

4. Financial Inclusion and Inclusive Growth

- Books:

- “Banks and Financial Inclusion in India: Policies, Priorities and Programmes” (Various authors/publishers)

- “Financial Inclusion” (Various authors, focusing on the Indian context).

- Policy Documents: Documents related to key government initiatives:

- Pradhan Mantri Jan Dhan Yojana (PMJDY)

- Business Correspondent (BC) model

- Reports on the role of Small Finance Banks and Payment Banks in inclusion.

5. Crisis, Reforms, and Non-Performing Assets (NPAs)

- Books by Banking Veterans/Journalists:

- Bad Money by Vivek Kaul (Focuses on the NPA crisis and Indian banking history).

- Overdraft: Saving the Indian Saver by Urjit Patel (Former RBI Governor, offering a view on NPAs and reforms).

- Yes Man: The Untold Story of Rana Kapoor by Pavan C. Lall (A case study on a recent private sector bank failure).

- RBI’s Asset Quality Review (AQR) documentation: The original circulars and discussions around the AQR of 2015.