Role of Money in a socialist Economy

Money is one of the foundational institutions of any economy — typically acting as a medium of exchange, a unit of account, a store of value, and a standard of deferred payment. Yet its role can vary significantly depending on the type of economic system in place. A socialist economy, characterized by state or collective ownership of the means of production and central planning, reconceptualises the functions and purpose of money in ways that distinguish it from capitalist systems.

While classical Marxist theory anticipates a future phase where money might wither away, in practical historical socialist economies money has continued to play essential functions, albeit under strong government regulation and within the framework of planning. This article explains how and why money continues to operate in socialist economies — how it differs from capitalist usage, and what functions it serves within planning, distribution, and economic coordination.

1. What Is a Socialist Economy?

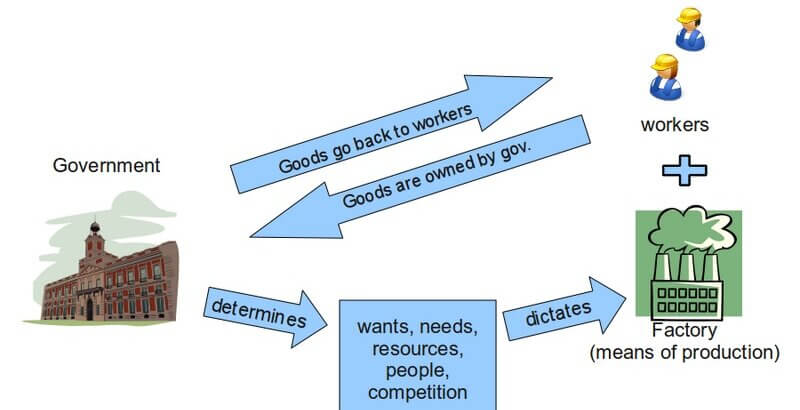

A socialist economy is an economic system in which:

-

The means of production – factories, farms, mines, and major industries-are owned collectively, usually by the state or cooperatives.

-

Economic activity is organized through central planning rather than by the free market.

-

Prices, production targets, and incomes are determined primarily through planning mechanisms rather than supply and demand forces.

Because of these foundational traits, the behaviour, functions, and purpose of money in socialist economies take on a different character than in capitalist market systems.

2. Historical Debate: Abolition or Transformation of Money?

Marxist theory contains debates regarding the future of money under socialism and communism:

-

Classical Marxist View: Marx predicted that in an advanced stage of communist society — beyond socialism — money might become redundant once production and distribution occur directly according to need rather than exchange value.

-

Practical Socialist States: In the 20th century, socialist states like the Soviet Union retained money and monetary calculation as necessary tools for planning and coordination, contradicting early hopes that money could be immediately abolished.

Historical experiments, such as early Bolshevik attempts to eliminate money after the 1917 revolution, showed that barter and non-monetary systems were impractical for complex economies. Money had to be reintroduced to stabilise production and distribution.

Thus, while revolutionary theory continues to debate the eventual disappearance of money, socialist economies historically adapted money for constructive planning and coordination.

3. Money in a Socialist Economy: A Different Concept

In a socialist system, money retains its formal functions — medium of exchange, unit of account, and store of value — but its social content and purpose change significantly compared to capitalism:

3.1 Universal Equivalent and Planned Value Measure

In socialist economies money serves as a universal equivalent -a common standard by which labour and goods can be measured across different industries and sectors. This is essential because a planned national economy must compare diverse outputs and inputs in a single unit for effective management.

Money in this context measures socially-necessary labour and enables comparison between different sectors, such as industrial production and agricultural output.

This function is critical for planning authorities to:

-

Determine whether enterprises meet their planned costs.

-

Compare actual performance against planned targets.

-

Identify inefficiencies and decide corrective measures.

3.2 Means of Circulation under State Direction

Money continues to act as a medium for the exchange of goods and services, but not through market competition or price fluctuations. Instead, circulation is directed by the central plan:

-

Enterprises and consumers use monetary transactions to trade goods.

-

Prices are set centrally, not by supply and demand.

-

Circulation is monitored to ensure planned production meets planned consumption.

This function supports economic coordination without relying on market price signals as the primary determinant of production decisions.

3.3 Means of Payment (and Public Finance)

Monetary payments in socialism flow through public and planned channels:

-

Wages, salaries, and bonuses are paid in money.

-

Enterprises repay planned loans to state banks.

-

Taxes and planned transfers occur through money.

The mechanism by which these payments occur helps the state to supervise economic behaviour and enforce plan compliance.

State banks control monetary advances, and the need to repay or justify funds creates financial discipline within the plan.

3.4 Instrument of Socialist Accumulation

In capitalist economies money and credit are often tied to private profit motives and capital accumulation. In socialist economies, money is used to accumulate productive capital for the collective benefit of society:

-

Enterprises keep money reserves in state banks.

-

These funds finance future investment, planned expansion, and reserve formation.

-

Savings deposited by the population are used for public investment.

This function underscores that money facilitates collective production growth and continual reproduction rather than profit maximisation for private owners.

3.5 Price Setting and Planning Facilitation

Under central planning:

-

Money enables planners to express and fix prices according to social priorities.

-

Prices embody value based on planned labour inputs rather than market competition.

-

Planners use monetary prices to allocate resources rationally within the plan.

This reflects a foundational difference: money facilitates planned economic allocation, not free-market allocation.

3.6 Store of Value, Savings, and Public Use

Money in socialism also serves as a store of value through savings:

-

People deposit earnings in savings banks.

-

These monetary savings are used by the state to support public goods and investment.

-

Money stored temporarily in banks recirculates through public credit mechanisms.

Thus, the store-of-value function is linked directly to planned economic reproduction and social welfare programs.

4. How Money Shapes Social Allocation

In a capitalist economy market prices allocate resources. In contrast, in a socialist economy monetary calculation supports central planning mechanisms:

-

Allocation decisions for “what,” “how much,” and “for whom” are made by state planners.

-

Monetary values express planned objectives and social priorities rather than private profit.

-

Resource distribution emphasises equity, employment, and welfare, not competition.

This shift means money no longer functions as an autonomous market signal, but rather as a tool of coordinated social planning.

5. International Trade and Money

Socialist economies engaged in international trade often used money not as a profit-seeking instrument but as an accounting and settlement medium:

-

Payments among states occurred using international currency or gold equivalents.

-

Monetary terms governed import and export settlements rather than speculative capital flows.

Thus, money enabled participation in global markets while domestic economic decisions remained within the planning framework.

6. Limits and Criticisms of Money’s Role

Despite the planned use, monetary mechanisms in socialist economies faced criticism and limitations:

6.1 Reduced Market Signals

-

Price signals were controlled, making real economic calculation harder.

-

Efficient resource allocation depended heavily on planning competence, not market feedback.

6.2 Bureaucratic Complexity

Central banking and monetary controls required large bureaucracies, creating delays and rigidities.

6.3 Long-Term Debates in Marxism

Some socialist thinkers argue that money should ultimately disappear when social production no longer requires exchange or value measurement — especially in advanced communism.

This theoretical perspective challenges the permanence of money within truly emancipated social systems.

7. Case Studies: Money in Historical Socialist Economies

7.1 Soviet Union

In the USSR:

-

The rouble acted as the national monetary unit.

-

Money was used for planning, payments, pricing, and accumulation.

-

Its value was stabilised by planned commodity supplies rather than market speculation.

7.2 China’s Socialist Market Economy (Post-Reform)

China reflects a hybrid model:

-

Money operates more like a traditional currency.

-

Market mechanisms influence prices and resource allocation.

Yet central planners still deploy money as an instrument of state-led objectives, combining planning and market elements.

This hybrid approach demonstrates the fluidity of monetary roles within contemporary socialist-oriented economies.

9. Theoretical Foundations: Marx, Engels, and the Question of Money

Understanding the role of money in a socialist economy requires revisiting the theoretical foundations laid by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels.

9.1 Marx’s Theory of Money

In Capital, Marx argued that money arises from commodity exchange and becomes the universal equivalent representing socially necessary labor time. Under capitalism:

-

Money transforms into capital.

-

Capital seeks surplus value.

-

Profit becomes the driving motive of production.

However, Marx distinguished between:

-

Lower phase of communism (socialism) – where money may still exist.

-

Higher phase of communism – where money and commodity exchange disappear.

In the lower phase, distribution may still be based on labor contribution — often expressed in labor certificates or monetary wages.

Marx did not provide a detailed blueprint for monetary abolition, but he predicted that once production was organized directly for use rather than exchange, money would gradually lose its function.

10. Socialist Planning and Monetary Calculation

One of the most important debates in economic theory is the “economic calculation problem,” famously raised by Ludwig von Mises and later expanded by Friedrich Hayek.

They argued:

-

Without market prices generated by competition, rational allocation of resources becomes impossible.

-

Money and prices in capitalism transmit decentralized information.

-

Central planners cannot gather and process all economic data efficiently.

Socialist economists responded by arguing that:

-

Planned pricing can reflect social priorities.

-

Modern statistical tools allow calculation without market chaos.

-

Money in socialism still provides accounting functions even without profit incentives.

This debate remains central to understanding why money persists in socialist systems — even if its purpose changes.

11. Enterprise Accounting in Socialist Economies

In historical socialist economies such as the Soviet Union:

-

Each enterprise had a financial plan.

-

Enterprises were expected to operate within budgetary targets.

-

Money functioned as an accounting control mechanism.

State banks monitored:

-

Loan repayment

-

Wage payments

-

Compliance with production targets

Thus, money served as an instrument of:

-

Cost control

-

Efficiency measurement

-

Plan enforcement

Unlike capitalism, enterprises did not operate for private profit but were evaluated according to plan fulfillment and social output.

12. Wages and Income Distribution Under Socialism

Even in socialist economies, workers received wages in money.

However, important differences exist:

12.1 Wage Determination

-

Wages are centrally determined.

-

Pay scales reflect skill, qualification, and national priorities.

-

Extreme inequality is minimized.

12.2 Social Wage

Beyond direct wages, citizens receive:

-

Free healthcare

-

Subsidized housing

-

Free or low-cost education

-

Public transportation support

Thus, money income represents only part of total consumption capacity.

In capitalist economies, access to goods depends heavily on income inequality. In socialist systems, redistribution through public services reduces dependence on monetary wealth.

13. Inflation and Monetary Stability in Socialist Economies

Inflation operates differently under socialism.

Since prices are centrally fixed:

-

Open inflation may be limited.

-

Shortages can appear instead of price rises.

-

“Repressed inflation” may occur when excess money circulates without sufficient goods.

The experience of the Soviet bloc showed that controlling money supply without flexible price mechanisms can create imbalance between purchasing power and available commodities.

Money, therefore, remains critical for balancing:

-

Consumer demand

-

Production capacity

-

State investment programs

14. Money and Consumer Markets

Although heavy industry dominated socialist planning, consumer goods still required monetary exchange.

Consumers:

-

Purchased goods in state shops.

-

Saved money in public banks.

-

Used money to access non-subsidized products.

Money allowed:

-

Personal consumption choice within limits.

-

Measurement of household demand.

-

Circulation of goods between urban and rural sectors.

Without money, even planned retail distribution becomes administratively complex.

15. The Gradual Transformation of Money in Communist Theory

Marxist theory suggests that in a fully developed communist society:

-

Commodity production disappears.

-

Distribution occurs “from each according to ability, to each according to need.”

-

Money becomes obsolete.

But this requires:

-

Post-scarcity production

-

Advanced automation

-

Abundance of goods

-

High social consciousness

Until these conditions exist, money continues to function as a transitional instrument.

Thus, socialism historically treats money not as eternal but as historically conditioned.

16. Comparative Analysis: Capitalism vs Socialism

| Function | Capitalism | Socialism |

|---|---|---|

| Medium of Exchange | Market-driven | Plan-regulated |

| Unit of Account | Reflects market price | Reflects planned price |

| Store of Value | Private accumulation | Public savings + social investment |

| Profit Motive | Central | Secondary or absent |

| Investment Driver | Private capital | State planning |

The fundamental distinction lies not in whether money exists — but in how and why it operates.

17. Money in Contemporary Socialist-Oriented Economies

17.1 China

Modern China combines:

-

State ownership in strategic sectors

-

Market pricing mechanisms

-

Monetary policy managed by the People’s Bank of China

Money plays a hybrid role:

-

Market-based transactions

-

State-directed investment

-

Global trade integration

China demonstrates that socialism in practice can incorporate monetary and financial tools without abandoning public ownership goals.

17.2 Cuba

In Cuba:

-

Dual-currency systems historically existed.

-

State planning remained central.

-

Money was tightly controlled.

Recent reforms have unified currency systems, illustrating the challenges of managing money in small socialist economies facing global market pressures.

18. Digital Planning and the Future of Money in Socialism

Modern technology introduces new possibilities:

-

Digital currencies

-

Real-time data analysis

-

Automated resource allocation

Some theorists argue that:

-

Artificial intelligence could replace price signals.

-

Digital accounting systems could minimize monetary reliance.

-

Blockchain-based systems could enable transparent public planning.

In such contexts, money may evolve rather than disappear.

19. Critiques from Within Socialist Thought

Even socialist economists acknowledge problems:

-

Monetary incentives may undermine equality.

-

Shadow markets may arise.

-

Bureaucratic inefficiencies may distort monetary signals.

Reformist socialism often advocates:

-

Limited market mechanisms

-

Flexible pricing

-

Monetary reforms to increase efficiency

Thus, money remains an evolving instrument within socialist theory.

20. The Ethical Dimension of Money Under Socialism

In capitalism:

-

Money symbolizes power and private wealth.

-

Wealth concentration reinforces inequality.

In socialism:

-

Money is ideally neutralized as a social tool.

-

Accumulation beyond social limits is restricted.

-

Redistribution mechanisms reduce wealth disparities.

Therefore, the ethical transformation of money is as important as its economic function.

21. Lessons from Historical Experience

Historical socialist economies demonstrate:

-

Money cannot be abruptly abolished.

-

Large-scale industrial coordination requires accounting tools.

-

Planning without monetary discipline leads to inefficiency.

At the same time:

-

Money need not serve private profit.

-

Financial systems can be subordinated to public welfare.

-

Economic democracy can reshape monetary institutions.

22. Conclusion: Is Money Compatible with Socialism?

The historical and theoretical record suggests:

-

Money is compatible with socialism.

-

Its functions are modified, not eliminated.

-

It becomes an instrument of planning, distribution, and collective accumulation.

While classical communist theory envisions eventual abolition, practical socialism has shown that money plays indispensable roles in:

-

Accounting

-

Coordination

-

Incentive structures

-

Public finance

-

International trade

The future of money in socialist systems likely depends on:

-

Technological advancement

-

Level of economic development

-

Political structure

-

Degree of social equality achieved

Money under socialism is not an engine of capital accumulation but a regulated mechanism serving social production and collective welfare.

The role of money in a socialist economy is fundamentally shaped by:

-

The existence of central planning and collective ownership.

-

The need for social accounting and coordination rather than private profit.

-

The use of money as an instrument of policy and planned distribution.

While money in a socialist economy retains its formal monetary functions, its purpose and implications differ dramatically from capitalist systems. Money becomes a tool of collective decision-making and planning — enabling production coordination, equitable distribution, and social accumulation.

While debates continue in Marxist and socialist thought about whether money should survive in a fully communist society, the historical record shows that money remains deeply embedded in socialist economic practice as long as production and exchange exist at scale.

Prices mechanism and socialism

The price mechanism plays a central role in economic systems. In capitalist economies, prices are determined primarily through supply and demand interactions in markets. In socialist economies, however, the operation of the price mechanism is fundamentally transformed. Rather than acting as a decentralized signal generated by competitive markets, prices under socialism are often administratively set, planned, or guided by social objectives.

Understanding how the price mechanism functions—or is modified—under socialism is essential to understanding broader debates about economic calculation, resource allocation, efficiency, and equity.

1. What Is the Price Mechanism?

The price mechanism refers to the process by which prices are determined in a market economy through the interaction of:

-

Supply

-

Demand

-

Competition

In capitalism:

-

If demand increases and supply remains constant → prices rise.

-

If supply increases and demand remains constant → prices fall.

-

Prices act as signals guiding producers and consumers.

According to Adam Smith, the “invisible hand” of the market coordinates economic decisions through price signals without central control.

Prices perform several functions:

-

Allocation of resources

-

Rationing of scarce goods

-

Incentive creation

-

Information transmission

In socialist theory, the key question is: Can these functions be achieved without free market pricing?

2. Socialist Critique of the Market Price Mechanism

Socialist thinkers, including Karl Marx, argued that market pricesunder capitalism reflect:

-

Private profit motives

-

Exploitation of labor

-

Class inequalities

-

Periodic crises

Marx distinguished between:

-

Use value (usefulness of a commodity)

-

Exchange value (market value expressed in money)

Under capitalism, exchange value dominates production decisions. Socialists argue that production should instead be based on social need, not profitability.

Therefore, the price mechanism in capitalism is viewed as:

-

Socially irrational

-

Crisis-prone

-

Inequality-producing

3. Price Determination in a Socialist Economy

n a traditional socialist system (e.g., centrally planned economy), prices are:

-

Determined administratively

-

Based on planned costs

-

Guided by social objectives

-

Stabilized over time

Rather than fluctuating daily with market forces, prices are set by planning authorities.

For example, in the former Soviet Union, the State Planning Committee (Gosplan):

-

Fixed prices for goods and services

-

Allocated raw materials

-

Determined wage scales

-

Controlled investment flows

Prices were often calculated based on:

-

Production cost

-

Target output

-

National priorities4. Functions of Prices Under Socialism

Even without a free market, prices in socialism still perform certain functions.

4.1 Accounting Function

Prices serve as a unit of account. They allow planners to:

-

Compare production costs across sectors

-

Measure enterprise efficiency

-

Evaluate investment decisions

Without monetary prices, economic calculation becomes difficult.

4.2 Distribution Function

Prices help distribute consumer goods. However:

-

Essential goods may be subsidized

-

Basic services may be free

-

Luxury goods may carry higher prices

Thus, prices become tools of social policy, not profit maximization.4.3 Incentive Function

In some socialst systems:

-

Enterprises were rewarded for meeting output targets.

-

Workers received bonuses.

Although rofit was not the primary motive, monetary incentives still existed.

5. The Economic Calculation Debate

One of the most significant criticisms of socialism came from Ludwig von Mises in his 1920 essay Economic Calculation in the Socialist Commonwealth.

He argued:

-

Without market prices generated by competition,

-

There is no rational way to allocate resources,

-

Central planners lack necessary information.

Later, Friedrich Hayek added that prices contain dispersed information about preferences and scarcity.

Socialist economists responded by suggesting:

-

Planning boards can simulate prices.

-

Trial-and-error methods can adjust production.

-

Statistical tools can gather economic data.

This debate remains central in economics.

6. Types of Pricing in Socialist Systems

6.1 Administered Prices

Fixed by government authority.

6.2 Shadow Prices

Used internally for planning efficiency.

6.3 Dual Pricing Systems

Observed in countries like:

-

China

-

Vietnam

These systems combine:

-

State-set prices for key goods

-

Market-determined prices for others

7. Price Mechanism in Maket Socialism

Market socialism attempts to reconcile socialism with market pricing.

Economists like Oskar Lange proposed that:

-

The state owns production.

-

Enterprises respond to price signals.

-

A central board adjusts prices to achieve equilibrium.

This is sometimes called the “Lange Moel.”

Here, the price mechanism exists—but without private ownership.

8. Strengths of Socialist Price Mechanisms

-

Price stability

-

Protection from inflation volatility

-

Ability to subsidize essentials

-

Reduced speculative bubbles

-

Focus on social priorities

9. Weaknesses and Challenges

-

Shortages due to miscalculation

-

Lack of consumer feedback

-

Overproduction or underproduction

-

Black markets

-

Reduced innovation incentives

In the Soviet experience, price rigidity sometimes caused:

-

Long queues

-

Product shortages

-

Hidden inflation

10. Modern Hybrid Models

Modern socialist-oriented economies often blend systems.

10.1 China

China’s “socialist market economy”:

-

Allows market pricing

-

Maintains state control in strategic sectors

-

Uses monetary and fiscal tools

The People’s Bank of China manages monetary policy.

10.2 Vietnam

Vietnam’s reforms (“Đổi Mới”) introduced market price mechanisms while preserving socialist political structure.

11. Ethical Perspective

In capitalism:

-

Prices reflect purchasing power.

-

Those with more money influence markets.

In socialism:

-

Prices can be adjusted to ensure universal access.

-

Essential goods may be priced below cost.

-

Distribution is based on social justice rather than ability to pay.

12. Can Socialism Function Without Prices?

Pure communism theoretically envisions:

-

No money

-

No prices

-

Direct distribution

However, in complex industrial societies:

-

Calculation without prices is extremely difficult.

-

Even planned economies rely on monetary units.

Thus, most practical socialist systems retain price mechanisms—though modified.

Conclusion

The price mechanism under socialism differs fundamentally from capitalism.

In capitalism:

-

Prices are market-driven.

-

Profit guides allocation.

In socialism:

-

Prices are planned or regulated.

-

Social need guides allocation.

While the free market price mechanism may be reduced or modified, prices continue to play crucial roles in:

-

Economic calculation

-

Resource allocation

-

Income distribution

-

Investment planning

Function of money in socialism

Money performs essential roles in every modern economy. Even in socialist systems—where the means of production are publicly or collectively owned and economic planning replaces market competition—money continues to exist and perform important functions. However, its role differs significantly from that in capitalism.

In capitalism, money is closely linked to private profit, capital accumulation, and market-driven price signals. In socialism, money is typically subordinated to social planning, collective welfare, and state regulation. This article explains the major functions of money in socialism, supported by economic theory and historical experience.

1. Money as a Measure of Value (Unit of Account)

One of the most fundamental functions of money in socialism is serving as a unit of account.

According to Karl Marx, money expresses the value of commodities in terms of socially necessary labor time. Even under socialism, goods must be compared and evaluated.

In planned economies:

-

Money measures production costs.

-

Enterprises calculate input-output efficiency.

-

National accounts are expressed in monetary terms.

Without money as a common denominator, comparing steel production with agricultural output or transportation services would be extremely difficult.

Thus, money enables rational economic calculation—even without market competition.

2. Money as a Medium of Circulation

Money facilitates the exchange of goods and services between:

-

State enterprises

-

Cooperatives

-

Consumers

In historical socialist systems like the Soviet Union, although production was centrally planned, consumers still purchased goods using money.

However, unlike capitalism:

-

Prices were often fixed by the state.

-

Markets were regulated.

-

Speculation was restricted.

Money therefore enabled circulation of goods while remaining under government supervision.

3. Money as a Means of Payment

Money functions as a means of payment in socialism through:

-

Wage payments

-

Salary distribution

-

Pension payments

-

Loan settlements

-

Tax transfers

Workers in socialist economies received wages in money, even though income inequality was generally smaller than in capitalist societies.

State banks monitored financial transactions to ensure compliance with national economic plans. In this way, money acted as an instrument of financial control and accountability.

4. Money as a Store of Value

In socialism, money also serves as a store of value.

Citizens:

-

Deposit savings in state banks.

-

Accumulate funds for future consumption.

-

Save for housing, education, or durable goods.

Unlike capitalism, where savings often fund private investment and stock markets, savings in socialist systems are typically redirected toward:

-

Public infrastructure

-

Industrial development

-

Social programs

Thus, money savings contribute to collective investment rather than private capital accumulation.

5. Instrument of Economic Planning

Money plays a key role in implementing economic plans.

Central planning authorities:

-

Allocate budgets to industries.

-

Monitor enterprise costs.

-

Adjust financial flows to meet national targets.

In planned economies, money serves as an accounting and supervisory tool. Enterprises must operate within allocated financial limits, which promotes cost discipline.

Money therefore becomes a technical instrument of coordination rather than a symbol of private wealth dominance.

6. Tool for Income Distribution and Social Justice

Socialist systems use money as a mechanism to promote social equity.

Governments may:

-

Subsidize essential goods.

-

Set price ceilings.

-

Provide free healthcare and education.

-

Redistribute income through taxation.

Unlike capitalist economies, where market prices often reflect purchasing power, socialist systems can modify prices to ensure access to basic needs.

Money thus becomes a tool for implementing redistributive policies.

7. Facilitating Socialist Accumulation

Money supports long-term economic growth under socialism.

State-controlled accumulation involves:

-

Reinvesting enterprise profits.

-

Financing heavy industry.

-

Expanding infrastructure.

Rather than enriching private shareholders, monetary surpluses are directed toward collective development goals.

This aligns with Marxist ideas that economic growth under socialism should serve society as a whole rather than private capital owners.

8. Regulation of Consumer Demand

Money helps regulate demand in socialist systems.

Since prices are often fixed:

-

Money supply must align with available goods.

-

Excess liquidity may cause shortages.

-

Controlled wages help balance purchasing power.

Thus, money plays a stabilizing role in preventing macroeconomic imbalances.

9. Role in International Trade

Socialist economies also use money in foreign trade.

Even highly planned systems must:

-

Import technology

-

Export raw materials

-

Conduct settlements in international currency

For example, during the Cold War, the Soviet Union conducted trade using state-controlled foreign exchange mechanisms.

Money in this context acts as an international accounting unit.

10. Differences from Capitalist Functions of Money

| Function | Capitalism | Socialism |

|---|---|---|

| Profit motive | Central | Secondary |

| Capital accumulation | Private | Collective |

| Price determination | Market-driven | Planned/regulated |

| Income inequality | High | Reduced |

| Investment control | Private investors | State planning |

The core difference lies not in the existence of money—but in its purpose and control.

11. Theoretical Debate: Will Money Disappear?

Marx suggested that in the higher phase of communism:

-

Commodity production would end.

-

Money would become unnecessary.

-

Distribution would follow the principle: “From each according to ability, to each according to need.”

However, most socialist economies have retained money because:

-

Complex industrial systems require accounting tools.

-

Resource allocation needs measurable units.

-

Complete abundance has not been achieved.

Thus, money remains a transitional but essential institution in socialism.

Expanded Academic References

-

Marx, K. (1867). Capital: Volume I.

-

Marx, K. (1875). Critique of the Gotha Programme.

-

Engels, F. (1880). Socialism: Utopian and Scientific.

-

Mises, L. (1920). Economic Calculation in the Socialist Commonwealth.

-

Hayek, F. (1945). The Use of Knowledge in Society.

-

Nove, A. (1983). The Economics of Feasible Socialism.

-

Kornai, J. (1992). The Socialist System: The Political Economy of Communism.

-

Soviet Academy of Sciences. Political Economy Textbook.

-

Ellman, M. (1989). Socialist Planning.

10. Lenin on money in socialist society: Political Economy, Economic Functions of Money.

11. “Role Of Money In A Socialist Economy”, IPL academic essay.

12. YourArticleLibrary on money roles in Soviet economic practice.

13. Scribd and academic outlines of monetary roles in planned economies.

14. Great Soviet Encyclopedia on accumulation and credit under socialism.

15. Reddit discussions on Marxist views of money and socialism.